You may have studied the descriptions of digital SLR technology in this article since you’re considering which DSLR to buy. Because technology changes so rapidly, it’s unlikely that the electronic camera you buy today will be your last. On the other hand, even the least expensive DSLR is a significant investment for most of us, especially when you consider the expense of the lenses and devices you’ll buy. You wish to make the right choice the first time. Digital SLR choice makers often fall under among 5 classifications:

■ Severe professional photographers. These consist of picture enthusiasts and experts who might currently own lenses and accessories coming from a specific system, and who need to maintain their financial investments by choosing, if possible, a DSLR that works with as much of their existing devices as possible.

■ Professionals. Pro professional photographers buy equipment like carpenters purchase routers. They want something that will get the job done and is rugged enough to work dependably in spite of heavy use and mistreatment. They do not necessarily appreciate cost if the equipment will do what’s needed, because their companies or customers are ultimately bearing the cost. Compatibility may be a great idea if a company’s shooters share a pool of specific devices, but a professional picking to switch to a whole brand-new system probably won’t care much if the old stuff needs to fall by the wayside.

■ Well-heeled professional photographers. Lots of DSLR purchasers show a high turnover rate, because they buy equipment mainly for the love of having something new and intriguing. Some actually feel that the only way they will have the ability to take decent (or better) images is to own the really most current equipment. I enjoy letting these folks have their enjoyable, since they are typically a good source of mint utilized equipment for the rest people.

■ Serious newcomers. Numerous DSLRs are sold to new photographers who are buying their very first digital camera or who have actually been utilizing a point-and-shoot video camera design. These buyers do not plan on junking whatever and purchasing into a new system anytime quickly, so they are more likely to examine all the alternatives and select the best DSLR system based on as many elements as possible. Their caution may be why they have actually waited this long to acquire a digital SLR in the first place.

■ Casual newcomers. As rates for DSLRs dropped a lot, I saw a new type of purchaser emerging, those who might have acquired a point-and-shoot video camera at the exact same price point in the past, and now have the concept that a DSLR would be cool to have and/or might offer them with better pictures. A lot of these owners aren’t serious about photography, although they might be severe about getting excellent photos of their household, travels, or activities. A large number of them find that a basic DSLR with its kit lens fits them just great and never ever purchase another lens or device. It could be said that a DSLR is overkill for these casual buyers, however many will wind up very pleased with their purchases, even if they aren’t using all the offered functions.

Questions to Ask Yourself when Buying a Camera

As soon as you choose which category you fall under, you need to make a list of your requirements. What sort of images will you be taking? How typically will you be able to update? What abilities do you need? Ask yourself the following questions to assist determine your genuine requirements.

Just How Much Resolution Do You Required?

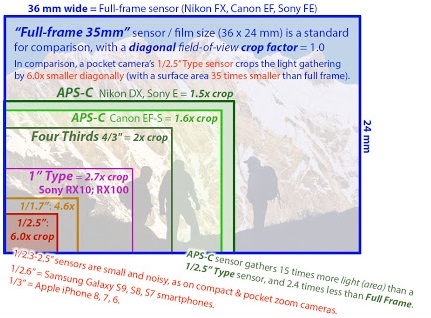

This is an essential concern since, at the time I write this, DSLRs are readily available with resolutions from about 10– 12 megapixels to 24 megapixels (and beyond, if you consist of some unique types called medium format cams). A lot more intriguing, not all digital SLRs of a particular resolution produce the exact same outcomes. It’s totally possible to get better photos from a 12 megapixel SLR with a sensor that has low sound and more accurate colours than with a comparable 12 megapixel model with an inferior sensor (even when the differences in lens efficiency is discounted). Looking at resolution in general, you’ll want more megapixels for some types of photography. If you wish to produce prints larger than 8 × 10 inches, you’ll be happier with a video camera having 12– 14 megapixels of resolution or more. If you wish to crop out small areas of an image, you might require a cam with 16– 21 megapixels. On the other hand, if your main application will be taking pictures for display on a websites, or you require thumbnail-sized pictures for ID cards or for a brochure with small illustrations, you might get along simply fine with the lowest-resolution DSLR camera you can find. Keep in mind that your requirements might alter, and you may later be sorry for choosing an electronic camera with lower resolution. Complete Frame or Cropped Frame? Throughout this chapter I’ve pointed out a few of the differences between full-frame sensors and cropped sensors. Your choice between them can be among the most crucial choices you make. Even if you’re brand-new to the digital SLR world, from time to time you’ve heard the term crop factor, and you have actually most likely also heard the term lens multiplier element. Both are deceptive and inaccurate terms used to describe the very same phenomenon: the reality that some electronic cameras (normally the most budget-friendly digital SLRs) provide a field of view that’s smaller and narrower than that produced by certain other (usually a lot more pricey) cams, when fitted with precisely the exact same lens. The picture rather plainly shows the phenomenon at work. The outer rectangular shape, marked 1X, reveals the field of view you may anticipate with a 28mm lens mounted on a “complete frame” (non-cropped) camera, like the Nikon D3-series or Canon 1Ds series. The location marked 1.3 X reveals the field of vision you’d get with that 28mm lens set up on a so called APS-H kind element cam, like the Canon 1D series. The area marked 1.5 X reveals the field of vision you’d get with that 28mm lens installed on an APS-C form element camera that includes practically all other non-Four Thirds /Micro Four Thirds designs. Canon’s non-full-frame electronic cameras, like the 60D and 7D, have a kind aspect of 1.6 X, which is virtually identical and likewise called by the APS-C classification. All 4 Thirds/Micro Four Thirds electronic cameras use a 2X crop aspect, represented by the inner rectangular shape. You can see from the illustration that the 1X performance provides a wider, more extensive view, while each of the inner field of visions is, in contrast, cropped. The cropping impact is produced since the “cropped” sensors are smaller sized than the sensors of the full-frame electronic cameras. These sensing units do not determine 24mm × 36mm; rather, they spec out at roughly 23.6 × 15.8 mm, or about 66.7 percent of the location of a complete frame sensing unit. You can calculate the relative field of view by dividing the focal length of the lens by.667. Hence, a 100mm lens mounted on an APS-C camera has the exact same field of vision as a 150mm lens on a full-frame camera. We human beings tend to perform multiplication operations in our heads more quickly than division, so such field of view comparisons are normally computed using the reciprocal of.667– 1.5– so we can multiply rather. (100/.667=150; 100 × 1.5=150.) This translation is usually helpful just if you’re accustomed to utilizing full-frame video cameras (normally of the film range) and want to know how a familiar lens will carry out on a digital camera. I strongly prefer crop aspect over lens multiplier, since nothing is being increased; a 100mm lens doesn’t “become” a 150mm lens– the depth-of-field and lens aperture remain the very same. Only the field of view is cropped. But crop factor isn’t better, as it implies that the 24 × 36mm frame is “full” and anything else is “less.” I get emails all the time from professional photographers who explain that they own full-frame cams with 36mm × 48mm sensing units (like the Mamiya 645ZD or Hasselblad H3D-39 medium format digitals). By their reckoning, the “half-size” sensors discovered in full-frame cams are “cropped.” Probably a much better term is field of view conversion element, however no one really uses that one. If you’re accustomed to utilizing full-frame film video cameras, you might discover it practical to use the crop aspect “multiplier” to equate a lens’ genuine focal length into the full-frame equivalent, despite the fact that, as I said, absolutely nothing is actually being increased.

How Frequently Do You Want to Update?

Photography is one field occupied by large numbers of techno maniacs who merely need to have the most recent and finest devices at all times. The digital photography world seldom disappoints these device nuts, because newer, more sophisticated designs are introduced every couple of months. If staying on the bleeding edge of technology is essential to you, a digital SLR can’t be a long-lasting financial investment. You’ll have to count on purchasing a brand-new electronic camera every 18 months to two years, since that’s how typically the average vendor takes to replace a current model with a more recent one. Some upgrades are minor ones. Thankfully, the common DSLR replacement cycle is a much longer schedule than you’ll discover in the digital point-and-shoot world, where a particular top of the line camera may be replaced every six months or more frequently. Digital SLRs normally are changed no more frequently than every 12 to 18 months– 12 months for the entry-level models, and 18 months or longer for the intermediate and sophisticated models. On the other hand, perhaps you’re not on a relentless quest for a shiny brand-new gizmo. You just desire excellent pictures. Once you acquire a video camera that gets the job done, you’re not likely to upgrade till you discover there are particular pictures you can’t take because of limitations in your existing devices. You’ll be happy with a cam that does the job for you at a rate you can afford. If your desires are large but your pocketbook is limited, you may wish to downsize your purchase to make those inescapable regular upgrades possible.

Sell or Keep your Devices?

Normally, come upgrade time, your old DSLR will deserve more as a hand-me-down to another user than as a trade-in. That’s why I’m currently eagerly anticipating using my present preferred DSLR as a second or 3rd video camera body when I do update to the next generation. An additional body can be available in convenient. When I leave town on journeys, I usually take one additional body just as a backup. Still, I end up using the backup more than I expected when I mount, say, a telephoto zoom on my “main” video camera and a wide-angle zoom on my backup so I do not have to switch lenses as typically.